Hungary Through Gastronomy

As Hungary steps out of the shadow of communism, it plans to attract more tourism by showcasing its excellent food and wine industries.

I arrived in Budapest on a warm September day and spent the first few hours in Hungary at the annual wine festival in the Buda Castle District. For only a few dollars, anyone could sample some of the lesser-known Hungarian wines alongside their more famous cousins like Bull’s Blood, a full-bodied red wine from the Eger region, and a vast array oftokajis–sweet Hungarian wines made from grapes shriveled to perfection byBotrytis, a fungus also known as noble rot. Since Hungarians call botrytized grapes aszu berries, most labels on these sweet, musty wines read Tokaji aszu.

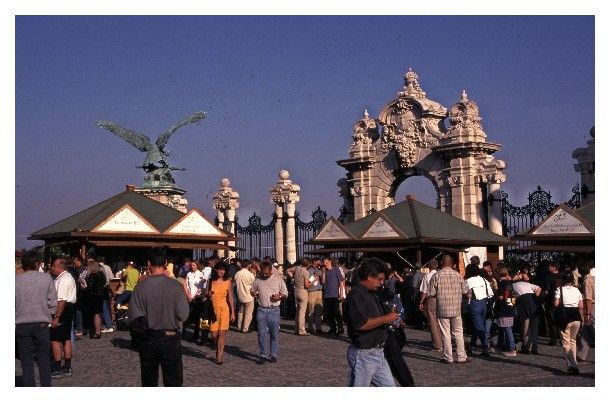

Budapest’s annual autumn wine festival is held in the Buda Castle district.

In the warmth of the autumn sun, I had my first sip of hárslevelü (pronounced “harsh leva lu”), a slightly sweet and golden wine fashioned from an ancient Hungarian white grape variety that gives the wine its name. Hars is the Hungarian word for linden; experts say the wine has the aroma of linden flowers. This lightaromatic wine became my favorite.

Surrounded by ruins from the Middle Ages, with a backdrop of the former royalpalace that now houses a national gallery and library, I got a favorable first impression of the quality and variety of wines Hungary has to offer, as well as thepride and breadth of this fast-growing industry. Later I would visit the Polgar winery in Villány, whose products were showcased at the wine festival.

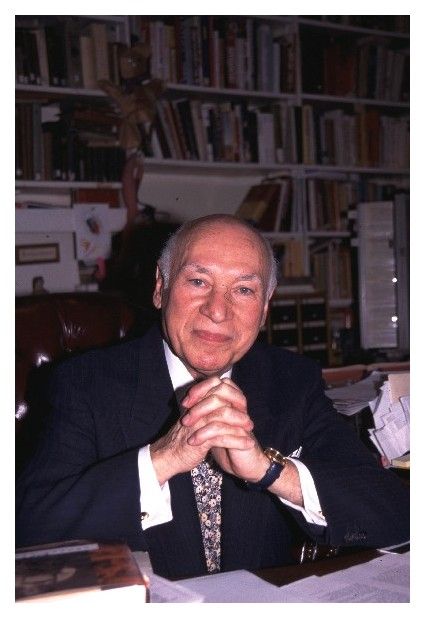

That evening, my first meal on Hungarian soil was atGundel, Budapest’sworld-class restaurant. It is co-owned by former U.S. ambassador to Austria Robert Lauder and Hungarian-born restaurateur and now New Yorker George Lang, who spends much of his time running one of his other eating establishments,Café des Artistes in Manhattan.

Though Lang is physically absent most of the time, his philosophies about food are ever present in the menu and atmosphere. He sees Gundel’s mission astwofold: to showcase traditional classic Hungarian dishes, such as a refined chicken paprika or a panfried fillet of perch from Lake Balaton (the largest lake in central Europe), and to offer the delightful results of cautious culinary experimentation.

Though Lang is physically absent most of the time, his philosophies about food are ever present in the menu and atmosphere. He sees Gundel’s mission astwofold: to showcase traditional classic Hungarian dishes, such as a refined chicken paprika or a panfried fillet of perch from Lake Balaton (the largest lake in central Europe), and to offer the delightful results of cautious culinary experimentation.

Like the French, the Hungarians love goose liver, as evidenced by the Gundel menu, which offers four house specialties. As an appetizer, we were tempted with a triad of gooselivers–including one marinated in a tokaji. Fear of fat may steer some diners away from goose liver, but it is a traditional appetizer for important meals and everyone in my party decided to eat like the natives. On reflection, I don’t remember seeing any obese people in Hungary.

Wines of Villány

Close to the Croatian border, the microclimate provides excellent conditions for the production of full-bodied red wines, promising visitors first-class wines on par with Bordeaux–for a fraction of the price. With that said, it does take some effort to get to the Vill ny area, which lies two hundred miles south of Budapest. (If you take the time to sample the area’s superb wines, make arrangements to stay overnight because Hungary has zero tolerance for drunk driving.)

Zoltan and Katalin Polgar run an amazing operation. Zoltan used to work in the local wine cooperative run by the government after the communists took power in 1946. But like so many others, he started his own enterprise when the system fell apart in 1990. While many small vineyards didn’t have the money to privatize, the Polgars have been extremely successful.

Just a short distance from the center of town, the Polgar winery is fitted with state-of-the-art fermentation equipment. During a quick tour, I saw stacks of wine cases destined for passengers aboardMalev, the Hungarian national airline, which features their wines. Around the corner lies their massive underground wine cellar, where they hold meetings for the local wine club and store wine for clients and friends in individual vaults naturally sheltered from temperature change.

Carved into the side of a volcanic hill in the nearby village of Villánykövesd is another, smaller cellar and a restaurant for winetastings. It was here that we toasted my birthday with twelve Polgar wines, including a Villány hárslevelü, a wonderfulrosé calledKadarka, and a ruby red Kekoporto fashioned from a Portuguese grape imported into the area in the eighteenth century.

Even though we were tasting wines well past midnight, Katalin was positive that no one would wake up with a hangover. “Good wines won’t give you one,” she said, and went on to explain that they use only 50 percent of the sulfite limit imposed by the EU and that most of the grapes are grown by organic methods. She was right.

Both Zoltan and Katalin are expert winemakers holding degrees in viticulture, but Katalin has taken on the role of spokeswoman. Over a simple meal of fresh farmer’s cheese, cured sausages, a paprika-flavored beef stew with tiny dumplings, stewed chicken with pasta squares garnished with sour cream, and cheese strudel for dessert, she spoke about one of her passions: the pairing of wine and food. In addition to their profession, the Polgars promote the Villány-Siklos Wine Road, a driving pilgrimage through the wine towns of the region.

On the Puszta

When the average American thinks of Hungary and food, one thing usually comes to mind: goulash, a stew of ground beef and pasta coated with a cheese/tomato sauce spiced with paprika–Hungary’sculinary calling card. On this trip, however, I would come to learn that American-style goulash is a woefully inadequate representation of true Hungarian gulyá s. Even an authentic gulyás cannot represent the culinary efforts of an entire culture, but it usually includes the three ingredients Lang identifies as the cornerstones of Hungarian cooking: onions, paprika, and lard.

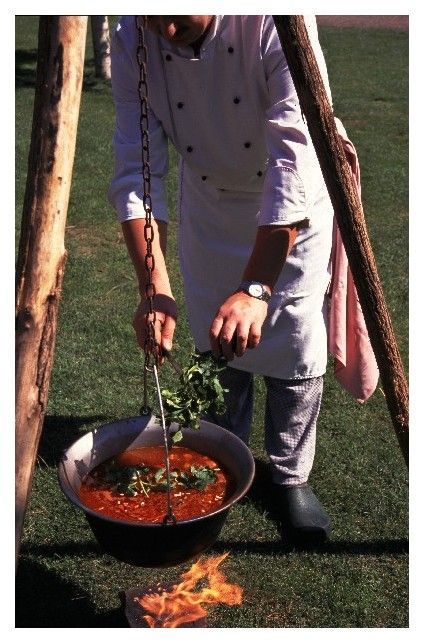

About a two-hour drive southeast of Budapest, and well worth a day trip, lies a flat, fertile plain commonly called the Puszta but more accurately referred to as theAlföld. Here in Lajosmizse, I would see my first real gulyás–a thin spicy soup, not a stew. This traditional gulyás was made with beef, onions, lecsó–a spicy Hungarian tomato/pepper condiment–potatoes, and small homemade dumplings cooked over an open fire in a heavy iron kettle.

About a two-hour drive southeast of Budapest, and well worth a day trip, lies a flat, fertile plain commonly called the Puszta but more accurately referred to as theAlföld. Here in Lajosmizse, I would see my first real gulyás–a thin spicy soup, not a stew. This traditional gulyás was made with beef, onions, lecsó–a spicy Hungarian tomato/pepper condiment–potatoes, and small homemade dumplings cooked over an open fire in a heavy iron kettle.

We were visiting Tanyacsárda, one of the many tcsárdas–rustic restaurants or inns–that dot the vastPuszta, occupying two-thirds of Hungary lying east of the Danube. Catering to large tourist groups, Tanyacs rda offers its guests a display of Hungarian horsemanship in a small rodeo, followed by a hearty meal served family style in an indoor/outdoor restaurant.

For the first course, we enjoyed the gulyáswe watched being made from start to finish. The main dish–served on a large wooden board–consisted of sauerkraut and potatoes topped with a variety of grilled, fried, and skewered meats served with a side salad of tomatoes, lettuce, and cabbage topped with a sweet dressing. Dessert was a delicious baked milk-and-egg pudding garnished with apricot jam and flambed with apricot brandy.

With satisfied stomachs, we got back on the road. Goose farms and paprika fields dot the landscape of thePuszta, and we made unplanned stops at both.Our unannounced arrival at a goose farm prompted the guard dogs to spring into action. Alerted by the commotion, the toothless watchman came out to greet us. We plied him with questions about the scrawny appearance of the several thousandbirds. As it turned out, the whole flock had just been plucked. Geese are hand-plucked an average of three times during their six-month growing period. Then they (and their livers) are fattened up before the slaughter. We decided to fully enjoy the pleasures of fine goose liver; it’s better not to know too much.

Next we visited Kalocsa, one of Hungary’s two main paprika-producing areas. After peppers were introduced to Hungary from theAmericas, via the Ottoman Turks occupying Bulgaria, they flourished in their new home. Eventually Hungary became famous for the paprika powder produced from red peppers.

Two varieties dominate the Hungarian paprika market–those fromKalocsa, which lies just east of the Danube, and the other fromSzeged, on the Tisza River. Kalocsa has a paprika museum as well as a popular beer hall–style restaurantfeaturing folkloric wall paintings and ethnic dancing by women in native costumes. Szeged is where the Nobel Prize–winning Hungarian biochemist AlbertSzent-Györgyi first isolated vitamin C. He later extracted large amounts of it from red peppers, despite the fact that he personally disliked eating them.

Millions of peppers are planted in the area’s rich alluvial fields every spring. Over the summer, ample sunshine and plenty of water for irrigation produce a bountiful harvest of these red jewels.Peppers are picked each autumn by teams of farmhands paid around seventy-five cents per pound. We stopped to photograph one team, which picked and posed for a while as we took plenty of pictures. Then they were happy to take abreak from the backbreaking work to pass around a flask of apricot brandy.

The peppers they picked that day would go through further ripening before being dried and ground into a powder exported around the world. Unfortunately,though I was surrounded by mounds of the fresh Hungarian peppers, I would have to be satisfied with paprika from last year’s crop, as it would be several weeks before the current harvest would be dried, ground, and packaged for sale. But while flavor may decrease slightly over time, I have never had a bad bunch of Hungarian paprika.

Driving through the Puszta, I was amazed to see so many New World plants. In addition to the ubiquitous peppers, potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, corn, andsunflowers are so common that I began to wonder what Hungarian cuisine was like before the Americas were discovered. I would get an answer to my question on the last day of the trip.

Back in Budapest

Before setting off to explore the capital city, we enjoyed a bountiful breakfast buffet at theArtotel, a new hotel on the Danube decorated with the contemporary works of American artist Donald Sultan. We filled up on such traditional foods as sausage, cheese, yogurt, and breads complemented by a large selection of items expected by the international clientele. But that didn’t discourage us from stoppingoff for coffee and dessert at Gerbeaud later in the morning. Coffeehouses likeGerbeaud, a nineteenth-century confectionery, are a Hungarian tradition designed to tempt travelers with their vast array of handmade candies and tortes.

China, antiques, and spas are popular attractions in Budapest, but not to be missed is the Central Market Hall, with its huge displays of paprika in attractive tins and cloth bags (perfect souvenirs or small gifts for friends back home), strings of dried peppers, canned goose liver, and a large section of folk crafts.

After our shopping spree, we had lunch at the Owl’sCastle, which resembles aTransylvanian manor house. Though it is owned by Lang, its atmosphere and foods are distinctive. The first noticeable difference is that the whole staff is female–both the waitstaff and everyone in the kitchen. The other noticeable difference is the menu, which features home-style cooking. Lang describes it as prewar Hungarian, not the classic dishes formerly served in upper-middle-class homes being revived atGundel.

Before lunch, we were treated to a special demonstration of how to make a traditional apple strudel. Two young women stretched pliant dough made from flour and lard–for which there is no substitute–until it was so thinthat I could read a newspaper through it. Then they added the filling and rolled the dough into a cylinder as long as the table. A few quick cuts made smaller rolls that would fit on a baking tray, which was whisked off to the oven. This was our dessert.

Before lunch, we were treated to a special demonstration of how to make a traditional apple strudel. Two young women stretched pliant dough made from flour and lard–for which there is no substitute–until it was so thinthat I could read a newspaper through it. Then they added the filling and rolled the dough into a cylinder as long as the table. A few quick cuts made smaller rolls that would fit on a baking tray, which was whisked off to the oven. This was our dessert.

On our last night, we had dinner at the Fortuna, located in the Buda Castle District. Fortuna has made a name for itself by using primarily pre-Columbian ingredients. Here one can enjoy a consommé of wild duck with saffron, sour cream, and a smoked quail egg, or a cream of chicken soup enriched with gosling liver and forty drops oftokaji. For the main dish, I indulged in a chicken strudel in a hárslevelü wine sauce with foie gras and ceremonial ragout of lamb, “as prepared by the ancient Hungarians for an offering.”

Fortuna’s menu is constantly fine-tuned by a board of chefs, winemakers, historians, ethnographers, archaeologists, journalists, and even doctors who are investigating the roots of Hungarian cuisine. One past research project focused on the spices, greens, and meats used in the court of Attila, king of the Huns. (The Huns were one of the early ancestors of the Hungarians, and Attila was their leader fromA.D. 434 to 453.)

After each project ends, the participants create an evening at Fortuna to present the “edible results” of their research, hopeful that some of the best dishes may find a place on the restaurant’s permanent menu. Finding an answer to my question about pre-Columbian cooking was a perfect ending to my stay in Hungary–a country with a fascinating cuisine that is becoming better known beyond its borders.

For more information:

Artotel Budapest

011-36-1-487-9-487, budapest@artotel.hu

George Lang, George Lang’s Cuisine of Hungary, Wings Book,

Avenel, New Jersey, 1994.

Hungarian National Tourist Office

212-355-0240 www.gotohungary.com

Michael Woods, “Albert Szent-Györgyi,” The World & I, December 1986.

Want to try a stove top goulash recipe? Cruise over to: https://www.jenreviews.com/hungarian-goulash/