Perched on the eastern edge of the North American continent, Newfoundland offers a bounty of wildlife, berries, good food, and kindred folk.

NASA satellite image of Newfoundland.

A winter burial used to be an arduous affair,” explained my driver, Greg Day, as we slowly pulled past a cemetery with neatly white-fenced plots. “After warming the ground by burning boughs and rubber tires, all the young men of the village would be conscripted to help dig the grave, sometimes through three feet of solid-frozen earth. It was an exhausting, whole-day event.” He drew in his breath at the end of the last sentence, as Newfoundlanders often do, seeming to emphasize the point.

His simple statement sums up so much about Newfoundland, a giant rock at the easternmost edge of North America.Though now one contiguous landmass, Newfoundland is really the by-product of varying geological forces. Amazingly, fossils on the southern tip of its Avalon peninsula at Mistaken Point link it to northern Africa, while other parts of the island are risen ocean floor or an extension of the Appalachians. Though the island possesses fish-rich rivers and forests, if you lose sight of the sea, you will seldom encounter people or habitation.

Three hours out of Toronto by air, Newfoundland comes into view. At first it seems a gray-green, somewhat duller version of Ireland, another northerly island in the Atlantic. But since it lacks the caress of the Gulf Stream, harsher features prevail. Rocks are more exposed, and vegetation is stunted. And I soon found out why natives don’t carry umbrellas: They are easily ripped to shreds by the volatile and unpredictable winds.

But as in most extreme environments, there are surprises. It turns out that the Vikings had good reason for calling the rocky island Vineland, for the whole island is covered with “little grapes.” Berries, to be exact. Berries of every persuasion–blueberries, cranberries, partridgeberries, bake apples, currants, dewberries, and bramble berries. In August and September, the natives reap a rich harvest from this bounty.

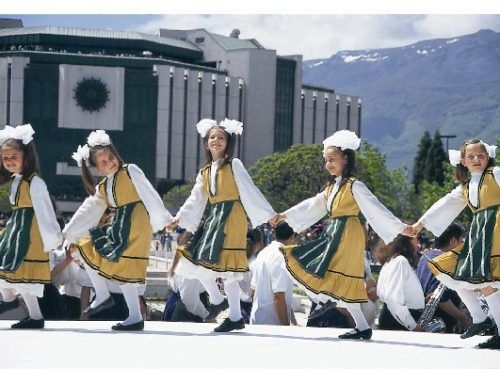

The author at the edge of the North American continent!

The last province (with Labrador) to join Canada in 1949, Newfoundland is inhabited by an independent and proud bunch. I found them charmingly insistent about the correct pronunciation of their beloved homeland. “Newfoundland, rhymes with understand” is a catchy phrase they employ as a learning tool. Without knowing it, most Americans pronounce the province “newfunlund,” with the accent on the middle syllable. Newfoundlanders stress the last syllable and say land the way it should be, not lund. You will be gently corrected until you get it right, which will probably take the better part of your trip.

Other than Corner Brook in western Newfoundland, the capital, St. John’s, is the only real city on the island. It claims one of the oldest streets in North America and possesses a sought-after port. When gale winds are raging on the high seas, St. John’s harbor is a haven to merchant and cruise ships alike.

Confusing St. John’s with St. John,New Brunswick, can be costly mistake. It’s not uncommon that a traveler bound for St. John unknowingly ends up stranded at St. John’s airport. And I’ve been told that Memorial University, located in St. John’s, has a very high faculty turnover rate, probably related to the lack of upscale malls and amenities on the island. That leaves St. John’s and Newfoundland for the hardiest and kindest of souls.

I came here to visit easternNewfoundland and to learn about the upcoming celebration, the five hundredth anniversary of the landfall of Italian navigator and explorer John Cabot, a.k.a.Giovanni Caboto. On the first leg of my trip, I stayed at St. John’s HotelNewfoundland. If you are on the right side, the rooms have a spectacular view of the harbor. After a delightful breakfast, head chef Steve Watson explained about some of the hotel’s regional cuisine. “If we took the Jigg’s Dinner off the menu, the natives would probably riot,” said Watson. And after tasting one,I know why.

A Jigg’s Dinner.

A Jigg’s Dinner is quintessential Newfoundland: It evokes memories of childhood, mom in the kitchen, and the population’s Irish roots. Whether the name comes from the lively dance or the method used to catch the local cod (i.e., to “jigg” by jerking up quickly on a line), the feast is the same. Salted beef is soaked overnight and the cooked for a few hours in fresh . Next, a Newfoundland pudding bag, filled half full with yellow split peas is placed in the pot. After another hour, potatoes, turnips, and carrots are added to the brew. When done, the peas are removed from the muslin bag and whipped with black pepper and butter to a delectable mash.

Especially delightful is the dish’s presentation–unique for what is basically a simple Irish dish. Each component of the meal is so well arranged that the pattern on the plate becomes a visual and gastronomical stimulus.

Visible from the hotel is Signal Hill, made famous by another Italian. It was here that Guglielmo Marconi received the first transatlantic wireless transmission from England in 1901. The hill overlooks city, sea, and harbor. Home to a museum, it is also a great vantage point to see icebergs and whales. In fact, this past spring, the “mother of all icebergs” perched itself at the narrows of the harbor, innocently causing one of the worst traffic jams St. John’s has ever experienced.

But my favorite spot in the St. John’s area was Cape Spear, the most easterly point of land in North America. I arrived between rain showers, with the sun shining, wind blowing, and a rainbow just forming over the water. I climbed to the top over an old World War II bunker guarding the entrance to the St. John’s harbor. With the wind rushing in my face, I took the time to ponder man’s perseverance against the robust forces of nature.

A new career

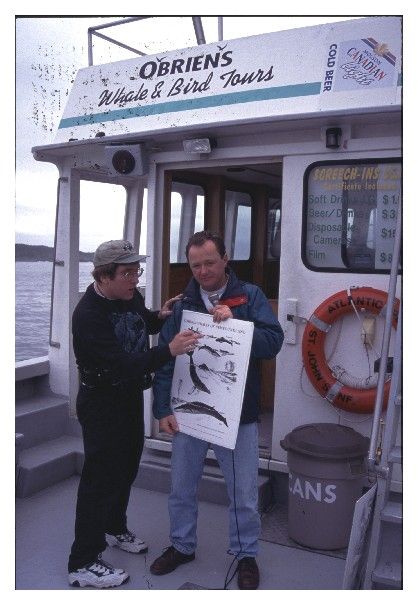

Looking for whales and puffins.

When Cabot arrived off Newfoundland in 1497, the ocean teemed with fish. Portuguese fisherman had been fishing the waters for years. Newfoundland’s fishery sustained its people until the mid-1980s, when the North Atlantic fish stocks, especially those of the GrandBanks, collapsed due to overfishing by international fleets.

Families who had fished for generations were forced to find other livelihoods. Many were forced out of fishing altogether, but the O’Brien family of Bay Bulls, about an hour’s drive south of St. John’s, has kept to the water by offering whale and bird tours to visitors.

Prone to seasickness, I was not really looking forward to the trip out to the nearby Witless Bay Ecological Reserve, but I climbed aboard the forty-two-foot vessel anyway. The boat plied past conifer-covered slopes set on triangular juts of vaulted sandstone, as Capt.Loyola O’Brien entertained the group with an Irish folk song and charts explaining the diversity of wildlife we would not be seeing on this particular jaunt. Unfortunately, by late September the two million birds that usually inhabit the island sanctuary had already departed for the winter, and the humpback whales and other marine delights would most likely be absent as well.

With the reserve finally in view,David Snow from Wildland Tours in St. John’s started pointing out the nesting sites of puffins, murres, kittiwakes, razor billed auks, gannets, and four types of gulls. It wasn’t too hard to imagine the cacophony that must accompany such a gathering. But with nests now empty, guano was the only real clue to former habitation.

I was especially disappointed by the absence of exotically plumed puffins, which I’m told are so ubiquitous in summer(95 percent of North America’s population nests here) that they are considered a provincial symbol. They seem to be wearing white T-shirts and black dinner jackets, with vivid orange markings on their beaks and feet and around their eyes.

Once back in port, we headed for the family-owned restaurant run by Ann O’Brien. A lunch of Newfoundland pea soup and meat cakes, accompanied by a cup of tea and a dessert of bread pudding topped with a light caramel sauce, did wonders to warm the bones and refocus the stomach.

Outports

“In the summer, I usually serve iceberg ice cubes in the morning orange juice, but unfortunately I just used the last piece of a big berg that drifted into the bay on my birthday, July 13th,” said Tineke Gow, owner of Campbell House. Decorated with period pieces and a touch of Tineke’s Dutch flair, the upscale bed and breakfast sits on the banks of Trinity’s Hogs Nose Bay.

Small towns like Trinity, nestled in bays and inlets along Newfoundland’s coast, are called outports. The term originally applied to ports other than London, but around 1820 the term was co-opted by Newfoundlanders to refer to any coastal settlement other than the chief port of St. John’s.

Trinity’s history is an encapsulation of the island’s. The Portuguese were probably the first Europeans to find shelter in Trinity’s ample harbor. Using the harbor as base, they fished the northern waters six months of the year. Beginning in the seventeenth century, the town forged strong ties with Poole, England, when businessmen came to make their fortune. Over the years, a series of merchants pioneered there before returning to the comforts of Mother England. Most prominent among them wasBenjamin Lester. At his death in 1802 he was the largest landowner in Newfoundland and a principal merchant in Poole. Soon, tourists will be able to visit the Lester-Garland home, which is being reconstructed from a pile of bricks.

Some of Newfoundland’s outports are only accessible by sea.

Modern-day Trinity, population 326, is going through a boom period. Townies–as St. John’s inhabitants are called–and others wanting a place to escape the hassles of modernity have recently discovered her tranquil shores and are snapping up properties and restoring them for summer and weekend homes. Tourism has increased through the entrepreneurial efforts of the Trinity Pageant, an open-air reenactment of the town’s history.Yet some things remain unchanged. The phone service can be compared to that of rural America, circa 1950. But this only adds to its charm.

Sipping tea by the fire in Campbell House, named for an Irish navigational teacher who built the house around 1840,I thumbed through a copy of the Dictionary of Newfoundland English (DNE), a fascinating compendium of Newfoundlandese with an eye-catching yellow dust jacket. The tome took three English professors twenty-five years to complete.The DNE contains authentic quotations from Newfoundlanders around the island(most dictionaries use literary sources), which are indicated in each entry and backed up by audiotapes filed in Memorial University’s folkloric archives. I highly recommend buying the book if you plan to read any regional literature.

O happy site

On the drive to Bonavista from Trinity, I asked Greg to stop the van for the tenth time. After leaping out and are fully traversing the rocks and rills, I tried to position myself for what I hoped would be the definitive picture of a Newfoundland telephone pole. Two poles are together, instead of the usual one, but the treatment is the same.Because permafrost doesn’t allow them to be dug far enough into the ground, the poles are propped up by rocks in a heavy-duty wooden box, a method called rock cribbing.

After snapping a few shots, we were back on the road to Bonavista. With its narrow lanes, beautifully fenced properties, and high-peaked houses, Bonavista is a typical Newfoundland outport.Legend is that in 1497 while in search of gold and spices for King Henry VII,Cabot sailed into Bonavista Bay and cried “o buon vista” (“o happy site”) on spying land. Of course, there were no houses then, but perhaps he was moved by the stark beauty of Newfoundland’s rocky, rugged landscape.

At the edge of town stands the Cap Bonavista lighthouse, which has been in operation since 1843. On June 24, 1997,a replica of the Matthew, the vessel Cabot captained on his historic voyage, will sail around the cape. As it passes the lighthouse and enters the harbor, it will be saluted by trumpets, brass bands, and applause from a crowd including the queen of England. Built in England, the new Matthew will sail from Bristol on May 5, 1997. After the three-day visit to Bonavista comes the celebration’s highlight: a forty-five-day circumnavigation of the island, with festivities in each port of call.

Another impressive tourist attractions in Bonavista is the soon to be completed Ryan Premises. Premises is a common word in Newfoundland; according to the DNE, it refers to “water-front property and stores, wharf, ‘flakes,’ and other facilities of a merchant,’planter,’ or fisherman.” (A flake is a structure made of poles on which fish are laid to dry.) At its zenith, the Ryan Premises contained retail and residential buildings, a salt fish processing facility, wharves, fish flakes, a barn, cooperage, sawmill and lumberyard, lobster factory, and powder magazine.

“Watch your step, ” warned Pat Buchanan from Parks Canada, as we entered what will become the premises’ retail shop. She promised that the huge shelves would be full of fishery-heritage merchandise by June. “It was only after we joined Canada that money became the preferred form of exchange in Newfoundland. For centuries, our fishing industry used a barter system based on the commodity of salted cod.Everything was valued relative to cod. Fishermen dealt with a central merchant who accessed their catch and gave them credits for supplies and food staples,” explained Buchanan.

From her words and from reading historical novels like Random Passage, by Newfoundland writer Bernice Morgan, one deduces that the cod trader, being the sole merchant, was almost as powerful as God in each Newfoundland fishery community.

Circumventing ladders and workers, we made our way into the former factory, where cod was processed and stored for export to Spain, Portugal, Italy, and the West Indies. Most noticeable was the scent of salt, a tangy aroma that impregnated the whole structure. I was compelled to think about the community’s historic and life-supporting connection to the ever-present sea.

The Ryan Premises will contain a museum, interpretative exhibits, and the retail shop. There will be live demonstrations of Newfoundland crafts such as furniture making and other skills integral to outport life since the 1700s–a testimony to Newfoundland’s east coast fishery.

Take some time to enjoy Newfoundland’s unspoiled beauty. In addition to the scenery and sea, you will be amazed at her unpretentious and friendly people. Though generations separate them from theirEuropean cousins, it is not uncommon to come across a Newfoundlander who seems just as much (or more) Irish as an Irishman, or more English than an Englishman.Though an ocean away from its origin, the rugged spirit of Celtic and Saxon culture has flourished in Cabot’s “New Found Lande.”