A visit to Sofia, Bulgaria, during a national holiday honoring Cyril and Methodius, the patron saints of the Bulgarian language.

A parade honoring Cyril and Methodius.

“What a perfect spot to set up shop!” I thought as we pushed past the Gypsy woman selling flowers on the church steps. We slowly made our way into Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in the center of Sofia for the official beginning of the festivities, a day I had been looking forward to for five years.

Ever since I first visited Bulgaria in 1990, I had wanted to be in Bulgaria on May 24 for the annual celebration of Cyril and Methodius Day, a tribute carried out by schoolchildren across the country to honor the two brothers who created the Cyrillic alphabet. Though the brothers proselytized and taught throughout eastern Europe, their memory is most revered in Bulgaria.

Bulgarians are exceedingly proud of Cyril and Methodius and claim the pair as their own. I cannot count the times I have been told that they were wholly Bulgarian, even though a quick look at any encyclopedia would cast doubt on that belief. Most entries say they were born approximately two years apart in ninth-century Thessalonica (modern-day Salonika), Greece, while other references say it was Macedonia. It is possible that they were ethnic Bulgarians born in Greece. Whatever the case, it is indisputable that their legacy was far-reaching and permanent.

They started their mission to spread Christianity among the Slavs in or around 863 and subsequently began to translate the Holy Scriptures into the language that would become known as Old Church Slavonic. In the process, they invented the Cyrillic alphabet, based on a combination of Greek and Hebrew characters. Modern Cyrillic alphabets include Russian (32 letters), Ukrainian (33 letters), Serbian (30 letters), and, of course, Bulgarian (30 letters).

For their contributions, Cyril and Methodius were later canonized by the Orthodox Church. Today, they are often referred to as the “apostles to the Slavs,” or by some as “equals to the Apostles,” making them eligible for the kind of awe and adoration reserved for the first followers of Christ.

Processions of children

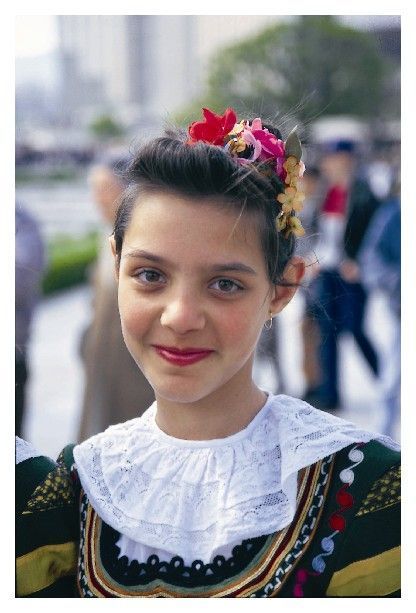

Beautiful Bulgarian girl at the festivities.

We caught the end of the announcements in the cathedral and had just enough time to light a votive candle before the crowd swiftly moved on to the next scheduled event a few blocks away. Here, students from all over the city convened in front of Sofia’s main library, which is named in honor of the two brothers. As the students gathered in the bright midmorning sun, it didn’t seem to matter that during Bulgaria’s years of complete communist rule, from 1947 to 1989, there had been a constant debate over whether they should be referred to as saints or merely siblings.

Two days before the holiday, schoolchildren start collecting greenery and branches of pine, boxwood, and bay trees, which they weave with flowers into garlands fifteen to twenty feet long for placement above their school’s entrances. They also make smaller wreaths to decorate large framed pictures of the twobrothers. Though these pictures appeared a bit unwieldy, the children proudly carried them this day in their procession, along with banners announcing their schools and Bulgarian flags.

After some fanfare, more announcements, and awards, the crowd moved through the city streets to the plaza of the National Cultural Palace, which was built in the 1970s under the direction of the daughter of the former longtime communist leader, Todor Zhivkov.

In typical Bulgarian fashion, two receiving stands were set up at opposite ends of the plaza. Supporters of the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF), a pro-democracy party, were celebrating at one end of the plaza, while the never-say-die communists delivered speeches at the other. By American standards, it would be like the Republicans and Democrats each holding separate Fourth of July celebrations, replete with fireworks, bands, and banners, at divergent ends of the Mall in Washington, D.C.

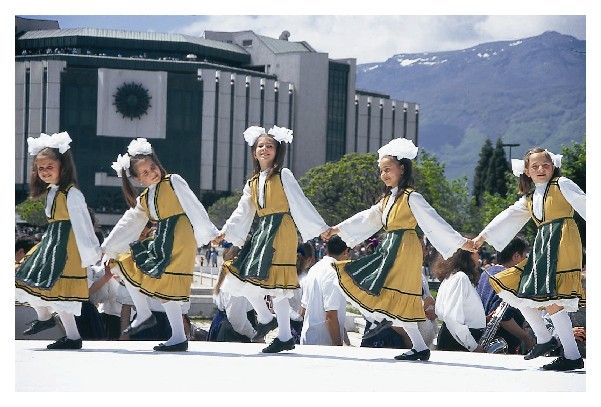

Traditional folk dancers on the plaza of the National Cultural Palace in Sofia.

At the UDF end, the crowd was treated to troupe after troupe of energetic traditional folk dancers from various schools around Sofia. With Mount Vitosha as a dramatic backdrop, beautiful girls dressed in traditional costumes danced and twirled in unison, while the boys, all so young and handsome, did the same.

The dancers were followed by single performers and choral groups composed of students and their teachers. The students wore white blouses or shirts, and the teachers, all solidly built women, wore pink. When the chorus started singing the official Cyril and Methodius anthem, composed in 1892 by Bulgaria’s national poet Stoyan Mikhailovsky, the whole crowd fell silent.

I have always been amazed at the Bulgarian enthusiasm for learning, reading in particular. Bulgarian homes commonly harbor books in five languages: Bulgarian, Russian, French, German, and English. With such enthusiasm for reading, what could be more basic than a celebration of the alphabet? Bulgaria has many national holidays and customs, but this celebration remains the most festive and joyous one, especially for students.

A former glory

Older Bulgarians like Tatyana remember far more elaborate May 24 celebrations, especially in smaller towns, before World War II and the subsequent conquest of Bulgaria by Soviet troops in 1944.

At that time, pupils with the highest grades led the class and carried the portraits of Cyril and Methodius. All the students marched in neat formation past the receiving stand, where the teachers, principals, and town officials (not Communist Party officials) proudly stood, as the school band played the Cyril and Methodius anthem.

One column of students, some carrying placards of individual Cyrillic letters, would barely have filed past the receiving stand, singing and throwing flowers to the men and women who had taught them the alphabet, before music from the next group filled the air. The parade eventually took them to the town square, where people dressed in national costumes danced the ruchenitza, a popular Bulgarian folk dance. It was here also that merchants and clerks, who at that time were considered to be people of means, handed out free candy and other delicacies. Everyone felt equal, joyful, and happy, according to Tatyana.

One column of students, some carrying placards of individual Cyrillic letters, would barely have filed past the receiving stand, singing and throwing flowers to the men and women who had taught them the alphabet, before music from the next group filled the air. The parade eventually took them to the town square, where people dressed in national costumes danced the ruchenitza, a popular Bulgarian folk dance. It was here also that merchants and clerks, who at that time were considered to be people of means, handed out free candy and other delicacies. Everyone felt equal, joyful, and happy, according to Tatyana.

In the afternoon, buses arrived at each school to take the children on a trip to a mountain lodge or some other scenic location. There they could play to their heart’s content or watch entertainment provided by pupils in the upper grades. All in all, the day was full of exciting and pleasurable events.

After their takeover of Bulgaria, the communists felt it was more important to mark their own celebrations. Cyril and Methodius Day was allowed to continue, though politicized, but in many Bulgarian minds it became a shadow of its former self. As I saw in Sofia, the students no longer march in an orderly fashion but form loose assemblies that fill the streets.

Despite such unfortunate twists of history, Bulgarians have never lost their reverence for Cyril and Methodius. Crowned with a halo of love by the entire nation, the memory of the two brothers has been preserved for more than eleven centuries. As Tatyana poetically reflects, it “will continue to be imbibed with the first drops of a mother’s milk as long as the words of the Bulgarian tongue are spoken on this earth.