The Four Corners of Kvarner

For a glimpse of the Mediterranean “as it was,” the northern Adriatic islands of Cres, Krk, Rab, and Pag are a good place to start.

The waterfront in the town of Cres on the island of Cres.

The Croatian islands that lie at the top of the Adriatic are popular vacation spots for natives, but they are yet to be discovered by the world. Their unfamiliarity is probably due to many factors, not the least being their relative inaccessibility. This could be a blessing in disguise, as these islands are almost untouched, some say much like the Mediterranean as it was before mass tourism left its mark around the basin.

Cres, Rab, Pag, and Krk are the four main islands of the tourist region of Croatia called Kvarner. This area is not limited to the archipelago of islands I visited; it includes an arc of fishing villages and cities along the mainland coast from Brestova, about twenty-five miles south of Rijeka, to just north of Senj. Ucka mountain and the Cicarija range separate Kvarner from the neighboring tourist region of Istria.

The word Kvarner is derived from the Latin quaternarius, which refers to the four cardinal points on a map. In this case, some sources say, it means that the waters of the region can be approached from all four directions: north, south, east, and west.

Like their southern cousins Korcula and Hvar, these islands are composed of limestone. Their streets are paved with this smooth, light-colored, and sometimes slippery stone, and it is also the primary building material for waterfronts, churches, and many dwellings. The four islands have another commonality: their main towns have the same name as the islands themselves. I quickly found out that this oddity, if not properly explained, can be a bit confusing when trying to chronicle one’s travels. I also found out that looks can be deceiving. Sun-splashed vistas can look warm, but after Labor Day cool temperatures coupled with a stiff breeze made me occasionally grab for my jacket.

Krk is the main jumping-off point for Cres, with regular ferries all day long, but there is also daily service from Rijeka. Although local officials have high expectations for tourism, they are not really geared up for it, which leaves much to improve, especially accommodations. One of the only places to stay on Cres is the Hotel Kimen, a postcommunist hotel with no shower curtains. Hence, a traveler must be a bit of an adventurer to settle for the lack of amenities and occasional surly service–and might be wise to make it a day-trip.

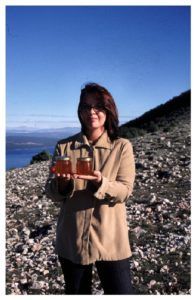

Cresian honey is a great souvenir.

Steep and inaccessible parts of Cres’ eastern coast are home to the white-headed vulture, or Gyps fulvus, which can usually be seen soaring high above the island as you approach from the sea. The northern town of Beli, whose ancient name was Caput Insulae, or “head of the island,” has a small ecomuseum dedicated to this bird, but it is really not worth the long ride unless you are also interested in visiting the nearby Tramuntana forest preserve. One worthy stop is a roadside stand on the way to Beli run by a young Cresian couple who sell sage honey.

Oddly, Cres has no aboveground streams, so the main source of drinking water is a lake in the middle of the island. Northern towns must resort to collecting rainwater. Beli’s forty-something inhabitants have refined the art of water collection, with sophisticated gutters and spouts on all the houses channeling the flow into a local cistern system.

The town of Cres has a nice waterfront with a few good restaurants and a Franciscan monastery with a collection of antique stone containers once used to store some of the island’s bounteous olive oil production. Again, the town offers little in the way of accommodations. Home stays are possible, but be prepared for the unexpected–such as bed-and-breakfasts that don’t offer breakfast.

A spot in the middle of the island boasts the oldest known Glagolitic, or proto-Croatian, writing tablet. The “tablet” was actually a headstone discovered in the cemetery of the St. Mark’s church outside the small town of Valun. Today, only replicas are on view at the cemetery and in Valun itself. Promoted as a resort, Valun, population sixty-eight, is definitely not a “Croatian Nice” as described by my overzealous guide.

Just off the town pier, I noticed freshwater bubbling to the surface from below, creating an interesting circular pattern on the water’s surface. While the island has no aboveground streams, this phenomenon suggests an extensive system of underground streams that make their way through the porous limestone geology, scientifically referred to as karst.

High speed on Rab

Rab is a relatively short distance from Cres by water, but there is no direct island-to-island service. Instead, you must retrace your steps by going back by ferry to Krk. Unfortunately, I did not have enough time to explore this fourth Kvarner island, which is famous for its white wine.

Krk was not the only glaring hole in my Kvarner travels. There was no time to visit Rijeka, Kvarner’s culture capital, or any of the villages along the coast. Instead, with an immutable deadline in Dubrovnik, my driver speedily traversed Krk, took the bridge back to the mainland, and then drove south along the coast a couple of hours until we came to the ferry for Rab. This trip might sound boring, but the vistas of the islands, water, and sky visible from the winding and, at times, precipitous coastal road were fantastic. During the summer tourist season, cars can line up for miles waiting for the ferry to Rab, but regular ferry service quickly shuffles them back and forth.

In ancient times, Rab was called Arba or Arbia, a name perhaps derived from the Latin arbor. In contrast to Cres, Rab is a green oasis nicely forested with oaks and pines and cultivated with olives and vegetables.

The town of Rab, on the island’s western coast, is built around a protected bay. It was alive with activity on the day of my visit and was the only place in my week of travels in the northern Adriatic where high-speed Internet access allowed me to catch up on my email. A computer-savvy local entrepreneur provided residents and travelers alike with connections to the outside world but, sadly, no coffee.

My guide and I looked around for a restaurant for lunch and settled for one with reasonable prices. In Rab, moderate prices do not mean modest portions. To the contrary, our order came with a heap of french fries, several kinds of broiled meats and specialty sausages, and plenty of fresh salad.

After lunch, much in need of a walk, we decided to explore. We strolled down Middle Street and then up a steep street to the top of town. Rab was filled with limestone churches–almost one per block–which definitely gives its six hundred or so inhabitants plenty of choices on Sunday morning. Four possessed prominent spires that towered over the town.

Before leaving the island, we drove to Lopar in the northwest. This village is famous for its long sandy beach rimmed by a grove of pines. The cooling shade helps make it a favorite vacation spot for families with children. It was well past the tourist season, so I was alone as I strolled in the shallow sea, watching the amazing pattern of ripples in the sand.

Moonscape for Cheese

As I approached Pag by ferry, it looked like a dry, deserted moonscape, but soon I could see that velvety, light-colored sage covered the hillsides. Pag is famous for a world-class sheep’s cheese that owes its unique qualities to the fact that the island sheep graze on this salt-washed sage. Called Paški sir, for “cheese from Pag,” this delicacy competes in taste and texture with Italy’s Parmigiano Reggiano.

Paški sir, a sheep’s milk cheese from the island of Pag.

The town of Pag is situated on a picturesque bay that resembles a lake. Its limestone streets echo with activity when the locals come out for a stroll after dinner or families bring their children to the city center to play ball. This sense of community is what I like most about Croatia. The residents all emerge from their houses to greet their neighbors, dinners are lingered over at home or in the local restaurant, and life is not lived in front of the television.

The island of Pag is more suited for tourists. There is much more to do and see than on Cres–although accommodations can be limited after Labor Day. Pag is synonymous with a handmade lace called paska cipka. I encountered many an older woman on her doorstep either making lace or trying to sell her handicraft. Though picture-shy, the lacemakers displayed their work proudly. Some large pieces can take months to make, so prices are not cheap. Bedspreads and tablecloths are astronomically expensive, but a small piece of Pag lace can easily be framed for a keepsake.

Another indigenous handicraft is koltra, which refers to the knitting of white coverlets that were traditionally part of dowries. On Pag, koltra are passed down from generation to generation and were once considered symbols of wealth and power. I didn’t see any for sale, but I was told that during World War II some families were forced to part with them to put food on the table.

Throughout history, Pag has been the site of a great saltworks, or solana, that is still operating today. The salt flats that lie at the southern edge of town are created by a naturally shallow basin from which water can evaporate quickly during the hot and windy summer months. Today’s owners produce sea salt for the table and a variety of scented bath salts. I only brought home a couple samples because salt is quite heavy.

Often, the evening meal on Pag, or in Pag, as the case may be, is followed by a glass of grappa, prosciutto, Paški sir, and friendly conversation at the local konoba, or cellar pub. It was in such a pub that I was invited to witness the ritual end-of-harvest grappa making. I couldn’t pass up the chance. I was driven to a dark street at the edge of town and led into a backyard shack containing a homemade still. Making grappa is not against the law in Croatia as long as it is for personal use, but somehow the operation still had a clandestine air.

The evening’s operation was well under way. The still was filled with a fermented mixture of leftover skins, seeds, and stalks from a local family’s wine production, to which had been added a handpicked and personalized selection of local herbs. The end result would be a year’s supply, or about forty bottles, of high-alcohol-content brandy with an earthy punch. In my mind, homemade grappa is the epitome of Croatian gôut de terroir, and is a perfect souvenir if you are lucky enough to wrest a bottle from somebody’s private stash.

Coral Island

On my way to Dubrovnik from Cres, Rab, and Pag, I took a nautical detour from the town of Sibenik to the tiny island of Zlarin, famed for its red coral. The word coral itself is derived from the ancient Greek korallion, which specifically refers to the precious red coral of the Mediterranean, or Corallium rubrum.

Two ladies with red coral necklaces.

For years I had heard that in Croatia the harvesting of Mediterranean red coral, locally known as crveni koralj, is primarily done in the waters of the Sibenik archipelago encompassing the islands of Zlarin, Obonjan, Kaprije, Zirje, and Krapanj. The town of Zlarin has been famed for its coral hunters since the fifteenth century. Initially, Zlarinians sold their catch to Naples, Venice, or Sicily, but an indigenous coral industry slowly developed. The island women were renowned for homemade coral objects, such as jewelry and detailing in folk costumes. Traditionally, coral has been harvested and crafted in the coastal areas of Croatia and sold inland.

In Sibenik and nearby Vodice, and later in Split, I visited several jewelry stores that displayed elegant branches of Corallium rubrum in their windows. Though most of what was for sale was a much paler coral from Japan–a subtle substitution about which only one shopkeeper was honest–I had high hopes for Zlarin. A forty-minute ferry ride off the coast at Sibenik, Zlarin is the childhood home of Toni Maglica, the owner of MagLite, whose return to the island is controversial. When I arrived at the dock, I was greeted by a local woman whose priority was to show me Maglica’s out-of-place “California-style” mansion at the edge of town. Apparently, a few too many trees had been bulldozed during construction, and, indeed, the public dock had been torn up by heavy-duty construction equipment. She feared, I think with good cause, the “Californization” of the Adriatic–or, put another way, the end of the island “as it was.” (Update: In a personal conversation with Maglica after this article was first published, I learned that the house in question is a villa built in the 1910s that he is restoring according the preservation statutes in place for such properties–blue shutters and all.)

After this short diversion, she gave me a personal tour of the local Catholic church and its coral-draped Madonnas and then led me to two shops in town that sell authentic oxblood-colored Mediterranean coral. Small coral factories were incorporated into both shops, but I saw little evidence of a thriving coral business–and couldn’t find anybody who dove for coral to talk with. Although they were selling real Mediterranean coral, there wasn’t much of it here at the epicenter of Croatian harvesting and production.

After this short diversion, she gave me a personal tour of the local Catholic church and its coral-draped Madonnas and then led me to two shops in town that sell authentic oxblood-colored Mediterranean coral. Small coral factories were incorporated into both shops, but I saw little evidence of a thriving coral business–and couldn’t find anybody who dove for coral to talk with. Although they were selling real Mediterranean coral, there wasn’t much of it here at the epicenter of Croatian harvesting and production.

Not too surprisingly, I would later hear that “they only play theater on Zlarin,” when it comes to manufacturing jewelry. My source, supposedly a world trader in coral and other semiprecious stones, hinted that most of the red coral plucked from the waters of the Adriatic goes to the Orient to be polished, thus saving on labor costs. Needless to say, I was disappointed: not with the island or its people but that a beautiful part of the heritage of Zlarin and, indeed, a treasured part of the Croatian culture might slowly be vanishing. But I will always treasure my Zlarinian red coral earrings as a memento of my travels among some of Croatia’s most undiscovered islands.

And as I look back at my time among these undiscovered islands, I have to wonder how, or if, they will find a middle ground between remaining “as the Mediterranean was” and incorporating a modicum of amenities that modern-day travelers expect. Indeed, that will be their challenge.

For travel information:

Croatian National Tourist Office

350 Fifth Ave., Suite 4003

New York, NY 10118

1-800-829-4416

www.croatia.hr

I would like to encourage the Croatian government to create a national Red Coral Museum somewhere along the Adriatic coast. I would also like to thank the Croatian National Tourist Board and Nena Komarica for assistance in the preparation of this article.