A sunny landscape, bounteous grapes, and a newfound freedom, make the Dalmatian coast of Croatia the perfect place to explore some excellent yet-to-be discovered wines.

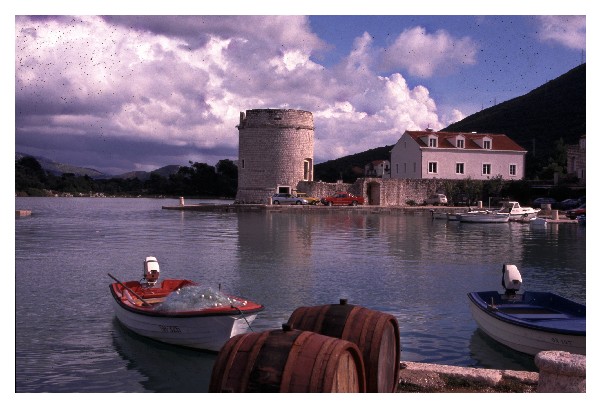

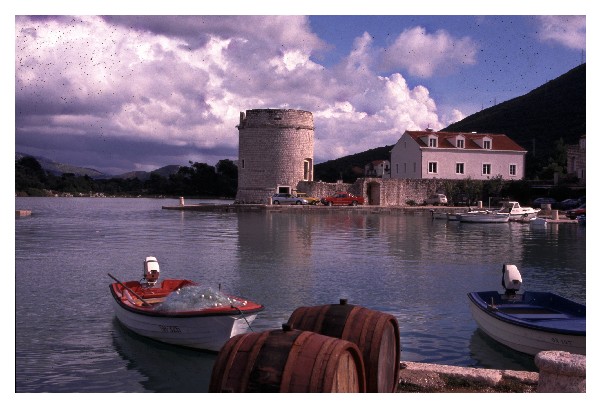

Water’s edge at Mali Ston, the beginning of Croatia’s Peljesac Peninsula.

“It has a marvelous color.” That was the beginning of my crash course on wine–and Croatian wines in particular.” Just hold the glass against a white background like your sleeve and notice how dark or pale it is,” explained Ed McCarthy, coauthor with his wife, Mary Ewing-Mulligan, of Wine for Dummies.

As the only travel writer on a trip with wine enthusiasts, wine critics, and wine journalists, I just sat and listened, soaking in the unexpected education on all things wine-related–barrels, fermentation, corks, vintage, viscosity, color (as mentioned), and, of course, grapes. I honestly can’t remember what wine was being discussed, and it doesn’t really matter. But after a week of seeing Croatia through the eyes of several wine authorities, I came away with a deeper appreciation for both the wine and the country.

Though I had traveled in southeastern Europe before, this was my first trip to Croatia, so I needed a primer on the country’s history and geography, as well as wine. A quick look at any regional map will confirm that its boomerang shape (some say crescent or flying bird) is a testament to regional struggles. But it was not always so oddly shaped. A thousand years ago it was round–encompassing modern-day Bosnia–prompting some staunch patriots to say, however politically incorrect, that Bosnia is the “heart of Croatia.”

As I studied a Croatian map, I quickly spotted a couple more geographical curiosities–a narrow stretch of Dalmatian coast at Neum conceded to Bosnia creates its only access to the sea, and Dubrovnik sits at the very southern tip of the country on a narrow strip of land that lies only a few miles over th e mountains from Bosnia.

Some historians say the whole Balkan mess started back in 1389 at the Battle of Kosovo when several Balkan kingdoms joined forces against the Turks but lost, ironically turning the battlefield into a sacred Serbian site. Even though the Turks won that day, the death of their leader and having to deal with invaders from the East delayed their return for 150 years, at which time the Ottoman Empire engulfed the entire region.

The end of World War II saw the creation of a “united Yugoslavia” under Tito, but the six republics (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia) retained their identity, and seminal animosities continued due to different religions and ethnicities. According to Albanian writer Ismael Kadaré, the author of Three Elegies for Kosovo, Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic began his demonic siege of modern-day Kosovo and the other former Yugoslav republics as some demented six hundredth anniversary of the defeat in 1389. From my point of view, the only positive result of that action was the subsequent breakup of Yugoslavia as Croatia and other republics quickly declared independence.

Croatia’s geography dictates three climates–Mediterranean, mountainous, and continental. The horizontal top half of the boomerang, where Zagreb is situated, is “on the Continent,” with cold winters and warm summers. The edge of the vertical bottom half of the boomerang forms the thin Dalmatian coast, while the country’s mountainous region lies a few miles inland.

It is said that 80 percent of the Dalmatian coast of Croatia is or will be dependent on tourism for its survival. An informed person would also add wine to that equation. With near-Mediterranean sunshine and warm temperatures, much of the coast there is perfect for wine production. In fact, the area experiences a double ripening effect–the direct sun from the south and southwest, as well as the sun’s reflection off the Adriatic.

Peninsula of wine

Nowhere does this equation work better than on Croatia’s Peljesac Peninsula, which branches off from the mainland an hour’s drive north of Dubrovnik. At a fork in the road at Mali Ston, we detoured onto the forty-mile-long peninsula, whose sunny southern slopes are perfect for viticulture.

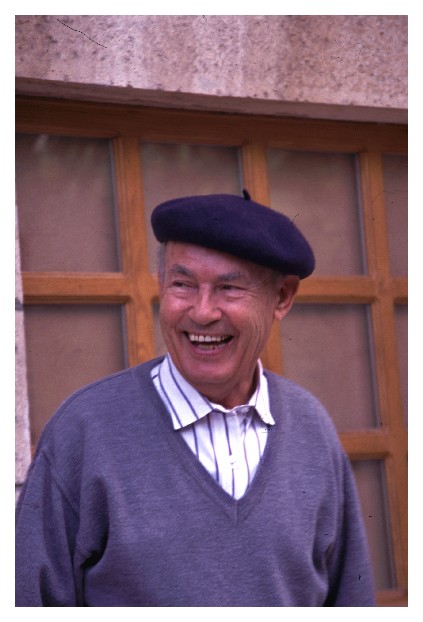

At Trstenik, we visited California vintner Mike Grgich, who returns to his native land part of the year to guide his new winery. As a young student of viticulture at the University of Zagreb, Grgich escaped communist Yugoslavia in 1954 and eventually ended up in California’s wine country in 1958. Two decades later, he would help catapult California wines to international acclaim when one of his chardonnays took first place in a blind taste test against French white Burgundies. Today he is co-owner with Austin Hills, of the Hills Bros. coffee company, of Grgich Hills Cellar winery, located in Rutherford, California.

A short, enthusiastic man with an appreciation for the ladies, Grgich is one of the most quotable personalities I’ve ever met. “Many times I compare wines to children because they are living things,” said Grgich, who is seldom seen without a beret. According to him, wines have five lives–the first in the vineyard, the second in fermentation, the third in an oak barrel, the fourth in the bottle, and the fifth in the glass.

“Wine and women have been kept in the dark too long,” said Grgich as he uncapped a bottle of his Plavac Mali, a deep-flavored and concentrated red wine coaxed from an indigenous little bluish grape of the same name. It was marvelous, but I liked even more his Posip, which is a dry white wine not unlike Pinot Blanc. The wine tasting at Grgich’s vineyard was a culinary event. His wines were served with thinly sliced prosciutto, Croatian bread, and regional cheese, all accompanied by Grgich’s infectious talk about all things wine related. I left with a growing appreciation for Croatian wine and an admiration for Grgich the mentor, who is passionately training a new generation of Croatian vintners–a true sign of the country’s unfolding democracy.

Grgich’s winery was our third wine stop in Croatia. Our group had first tasted wines in a castle outside Zagreb. Regional wines around Zagreb are predominantly white, due to the area’s Continental climate, which produces much less sunshine than along the coast (white grapes take less sunshine to mature). Some of the Continental wines were acceptable from my humble point of view, but none are available in the United States due to low production levels.

Our second encounter with wine was within the magnificent walled city of Dubrovnik. With international help from organizations like the Washington, D.C.–based Rebuild Dubrovnik Fund, the city is rapidly recovering from the intensive shelling it endured at the hands of Milosevic a few months after it declared independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991. Some saw the insane bombing of this UNESCO World Heritage Site as his desperate attempt to secure another seaport for Serbia in addition to those in Montenegro.

We walked the ancient city wall, which gives you a bird’s-eye view of the city, and then descended to wander the ancient limestone streets. Always in the mood to visit a local market, I was fascinated by an old woman who sold dried figs strung on a wreath with bay leaves. We nibbled on the figs as we toured historical sites like the second-oldest European apothecary, which is housed in a fourteenth-century Franciscan monastery.

That evening, a few of us roamed into a modest store in search of bottles of Dingac, another Croatian red wine of great repute. Though it is available in the United States along with Grgich’s wine and another outstanding red wine called Postup, we were all looking for bargain bottles.

Unfortunately, tourist prices prevailed, but the surprise of the store was its homemade wine, Domaci vino. Behind a humble counter two large stainless steel tanks were filled with batches of fresh wine–one red, one white. For the unbelievably low price of a dollar a bottle, we bought several, one to share over dinner and the rest to take home. This modest, unadvertised wine turned out to be some of the most refreshing and clean-tasting wine I had ever sampled.

The wine islands

As a six-inch-deep river of rain cascaded down normally dry, sun-drenched limestone steps, one of the guides from Atlas, the leading travel company in Croatia, confessed, “I’ve been to the island of Hvar a hundred times, but this is the first time I’ve seen it rain.” It rained torrents for about twenty minutes, and then the sun came out once again. In Hvar’s harbor–the main city bears the same name as the island–the accompanying wind had stirred up gentle waves that washed the wide limestone sidewalks lining the shore.

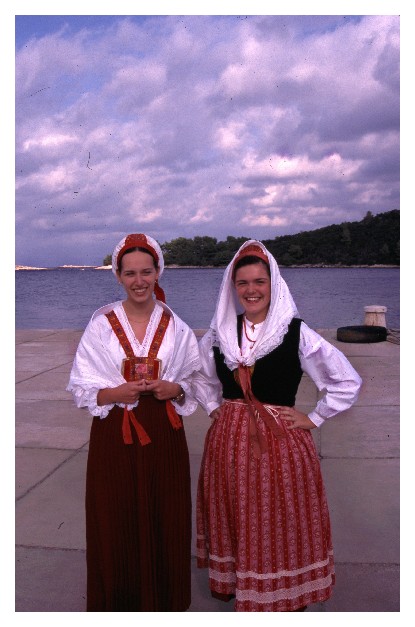

The moment we arrived in Hvar it became obvious what it’s famous for, because hawkers lined the dock to sell their lavender wares–sachets, l’eau de lavender, lavender oil, and lavender honey. Lunchtime at the Junior restaurant was spent tasting some dishes of mouth-watering local seafood accompanied by excellent wines grown on Hvar’s southern slopes in odd-sounding vowelless towns like Vrh.

If you have time to get off the beaten path on Hvar, do so, because away from the tourist areas you will find individuals who sell homemade wine and lavender goods from their homes. We did just that on a bus ride over the mountains to meet our transportation on the other side of the island. The undulating countryside was magnificent, and I was told that if we’d come in the middle of summer the hills would have been purple with lavender.

Hvar was the third Dalmatian island we visited traveling from the Peljesac Peninsula to Split by Russian hydrofoil. Our first stop had been Mljet, the southernmost island, rightly called one of the “green islands” for its verdant vegetation. It is mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey and Saint Paul’s writings, and the western third of the island has been designated a Croatian national park.

We took a short boat ride on the smaller of the island’s two saltwater lakes formed by the sea entering into limestone karst formations. Our destination was an ancient, now-abandoned Benedictine monastery on a small island within the island. Aleppo pines grew so close to water’s edge that their branches touched the surface. Mljet is a peaceful island with no commercial wine production, but it’s famous for sheep cheese, olive oil, and honey. In fact, the island is probably named for melita, the Croatian word for honey.

Our next stop was Korcula–my favorite among the islands we visited and the supposed birthplace of Marco Polo. If you didn’t know that fact you would quickly suspect it, because all types of local businesses have incorporated Marko Polo [sic] into their names. After checking into our barely postcommunist accommodations in the island’s capital, you guessed it, Korcula, we embarked on a bus excursion to the island’s top wine-making town, Lumbarda.

In Lumbarda, we visited winemakers Maja and Branmir Cebalo who make a wine named after the island’s most famous grape–Grk. (That’s pronounced “gurk” which rhymes with “kirk.” If you travel to Croatia, you will soon find out that it is famous for words without vowels, but Grk remains my favorite, second only to the island Krk.)

As we walked from the bus up his driveway lined with grape vines, we spotted the vintner’s mother-in-law with an armload of cabbages. The area’s reddish Pleistocene sand, so small grained it was as if it had been sifted through the hand of God again and again, is perfect for growing cabbages, as well as grapes.

“I love red wine,” said Maja, a short dark-haired woman with a brilliant smile, “but in Zagreb as a student I longed for Grk.” My brother-in-law, then a friend, promised to serve a case of the best Grk at my wedding, and then he introduced me to Branmir–his brother, the winemaker.” You can figure out the rest of the story.

On the Cebalo’s arbor-roofed backyard patio, we tasted some of their unique wines crafted from Grk, an indigenous white grape, and other local grapes As we quaffed, we talked about wine growing on the island. The Greeks established the first vineyards on Korcula in the third century, B.C. (In fact, some islanders speculate that the word “Grk” may be refer to a person from Greece.)

“During the communist years, private individuals on island, and throughout Croatia, were limited to making wine for the state and their own consumption,” explained Branmir in a staccato English that Maja was quick to decipher for us. Branmir went on to explain how only recently Croatians had had the freedom to attempt the commercialization of more than an estimated 270 types of Croatian varietal grapes.

Experts believe Croatian grapes have great potential. For example, through DNA profiling, Carole Meredith, a professor of viticulture at University of California-Davis, recently discovered Zinfandel is a close relative of Grgich’s beloved Plavac Mali. Their exact origin, and how or when Zinfandel grapes arrived in California is a mystery, but their genetic connections shows the latent potential that other yet-to-be-harnessed Croatian varieties may have in becoming the cornerstone of wine production around the world.

In addition to yielding a splendid table wine, the Cebalos also use Grk grapes to make a sweet dessert wine. But we all loved, and took bottles home of, their red dessert wine called prosek made from dried Plavac Mali grapes. (Sorry, it’s not available in the United States, but sold at the door of the Cebalo home to those who know what to ask for.) While prosek will probably remain a regional offering, the Cebalos hope to increase their production of Grk in order to export. But that will take some hard-to-come-by investment dollars for much-needed new fermenting, aging, and bottling equipment.

I had hoped to depart the Cebalo vineyards with a bottle of their Grk, but we had just drank the end of last year’s wine and this year’s vintage was still in the barrel, so I had to pick up another bottle of Grk at the airport in Zagreb.

This precious bottle of Grk made it through Heathrow and U.S. customs, but met its doom at Dulles airport. As I ran to catch the airport bus, my beloved bottle flipped out of my purse and smashed on the ground. Too mad and exhausted to pick it up, I left it behind and boarded the bus muttering some choice expletives under my breath. Several weeks later I eventually received a replacement bottle from a Croatian friend, but anxiously await the time when Grk will be available in the States.

Perhaps the Croatian government should capitalize on the odd-sounding name Grk and the rhyming island of Krk, for an introductory wine campaign in America. I can see it now. A full-size standup poster of Grk and Krk, two disgruntled ex-freedom fighters who look like they have just come down out of the Croatian hills, beckon you to try their wine. And, of course, you’d have to buy two bottles–one white (Grk) and one red (Krk).

Lamentably, I’ve been informed that there’s only white wine on Krk, but someday, next to other fine European selections from France, Italy, and Spain, I hope to find a wide range of Croatian wines on American shelves. Grk and Krk will be proud.

Importers of Grgich’s Croatian wines:

Monsieur Touton Selections

129 West 27th St., Suite 9B

New York, NY 10001

(212) 255-0674

Croatian National Tourist Office

1-800-829-4416