The New Chocolate Revolution

I knew we’d been invited to be wined, dined, and brainwashed about chocolate, but little did I know how much we’d be educated. Most attendees at a at 2001 conference hosted by the American Chemical Society at their conference center outside Baltimore knew the basics–but I, for one, didn’t know that the sumptuous taste of chocolate can largely be attributed to the process of fermentation. That’s right, fermentation. In fact, the flavor and quality of chocolate are wholly dependent on a milieu of silent factors, including the blend of cacao beans chosen for a particular chocolate, its roasting, as well as growing and fermentation practices.

I knew we’d been invited to be wined, dined, and brainwashed about chocolate, but little did I know how much we’d be educated. Most attendees at a at 2001 conference hosted by the American Chemical Society at their conference center outside Baltimore knew the basics–but I, for one, didn’t know that the sumptuous taste of chocolate can largely be attributed to the process of fermentation. That’s right, fermentation. In fact, the flavor and quality of chocolate are wholly dependent on a milieu of silent factors, including the blend of cacao beans chosen for a particular chocolate, its roasting, as well as growing and fermentation practices.

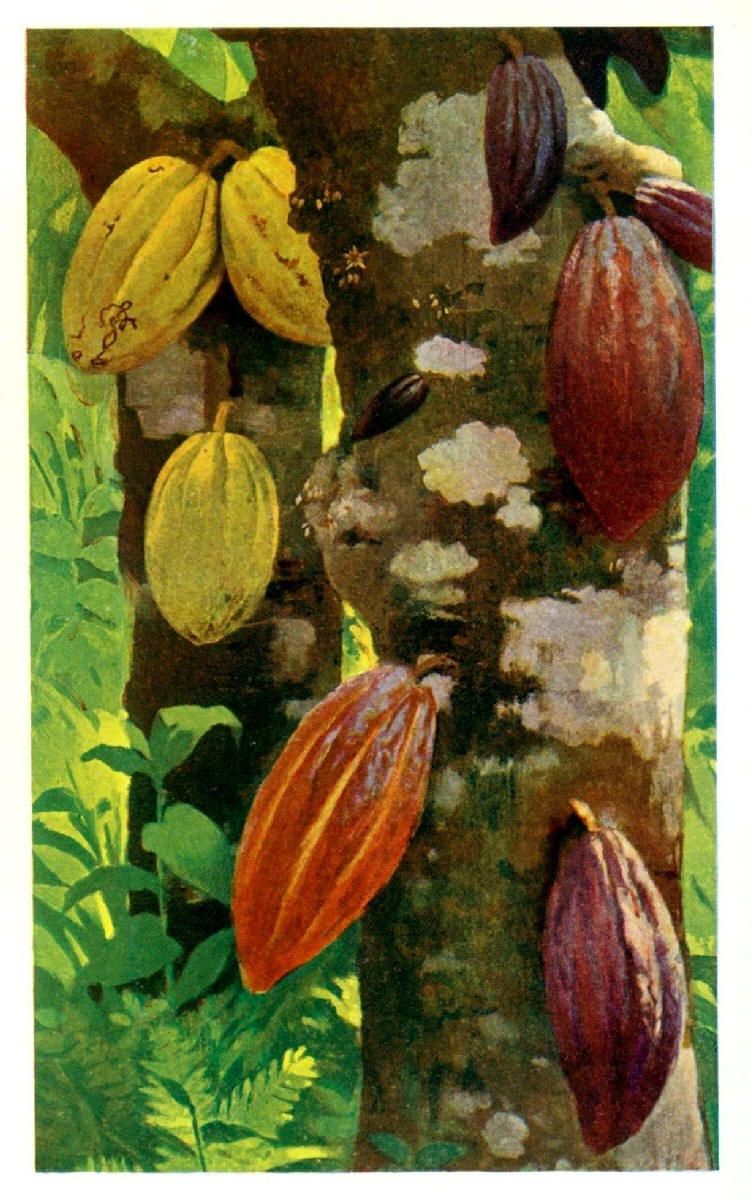

Harold McGee, wizard scientist and the author of On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, surprised and educated the audience with pictures of cacao beans before and after fermentation. Beforehand, the beans, which are really cotyledons (or embryos) for a new cacao plant inside a large pod, are almost colorless and look and taste nothing like chocolate. But after a cadre of bacteria, fungi, and yeasts indigenous to the tropics–that’s why fermentation can’t be done elsewhere–work their magic in situ, the beans take on a purplish-brown hue and the taste we associate with chocolate. We all chuckle when we hear the phrase “death by chocolate,” but ironically it’s really “chocolate by death”–the death of the embryo marks the beginning of chocolate’s flavor.

Since cacao can be grown and fermented only within twenty degrees of the equator, most chocolate companies import the fermented beans and do the final stages of preparation–roasting, refining to reduce sugar crystal size, and conching, a final “kneading” of the chocolate to expel volatile acidic gases that are a by-product of fermentation–in their home country. So Swiss chocolate is not really from Switzerland, French chocolate is not truly French, and Belgian chocolate isn’t from Belgium, but, as you will see, Venezuelan chocolate is truly Venezuelan.

We also learned about chocolate’s antioxidant effects. According to Joe Vinson, professor of chemistry at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania, it has more antioxidants than spinach does. (He defines an antioxidant as any substance that prevents the oxidation, and hence the creation of damaging free radicals, of substrates like proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates.) The antioxidants in chocolate are called polyphenols. If true, this information should free devoted chocoholics from undue guilt.

In fact, while unfermented cacao beans contain about 8 percent polyphenols, the amount goes up with fermentation. According to Vinson, a standard-size milk chocolate bar has approximately the same quantity of antioxidant polyphenols as a five-ounce glass of red wine. (We’ll all toast to that!)

More revelations

McGee’s fermentation revelations and Vinson’s polyphenols got me thinking about chocolate. I already knew there was a wide range of quality, with some so-called chocolate bars not even containing cocoa butter, a vital ingredient that imparts silkiness and that melt-in-the- mouth quality to chocolate. Substitutes like palm kernel oil just don’t measure up. (Coincidentally, this is a huge issue for the European Union.)

With a little probing, I found out that some chocolate manufacturers are at the forefront of a revolution to make chocolate as distinctive as fine wine. Assisting them are experts such as Maricel Presilla, food historian, importer of heirloom cacao, and the author of The New Taste of Chocolate. Presilla also serves up great chocolate desserts at Zafra, her restaurant in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Presilla oriented me with a short history lesson on the progression of events in the chocolate world over the past few decades. A minirevolution started when some old European chocolate companies started to mass-produce chocolate bars for chefs. Chef-friendly bars by Callebaut of Belgium had a cacao content in the comfortable fifties (a 50 percent combined cocoa and cocoa butter content) and helped chefs easily duplicate their recipes. Then came Valrhona of France, which offered more complexity and deeper-tasting chocolates.

Callebaut uses mostly African beans, while most of Valrhona’s chocolates are blends created with high-quality beans from Venezuela and Trinidad–each one was considered a work of art with a more sophisticated palette of flavor. Callebaut was sold to Swiss chocolate giant Toblerone in 1980 and was later resold to Swiss businessman Klaus Jacobs and renamed Barry Callebaut when it bought out Cocoa Barry in France. Today Callebaut still makes great bulk chocolate for baking. Known as couverture. it is widely used in hotels and restaurants. With about twenty factories, Callebaut is probably the second leading chocolate mover in the world, just behind ADM Cocoa, the cocoa commodities division of Archer Daniels Midland.

Established in 1921, Valrhona is owned by a group of French investors and has its headquarters in the Rhone valley. “We own plantations in Venezuela and grow our own beans. We do everything from A to Z, except use pesticides or chemicals,” says chief operating officer Bernard Duclos. “Just as for wine, the land has a big influence on the finished product. We add Trinidadian beans to those from Venezuela to impart a floral bouquet to the finished cacao.

“If you tour our only factory in Provence, it’s almost like Willy Wonka. Old machines are making a lot of noise. We use old recipes and techniques to make vintage chocolate,” explains Duclos. “Every chef is an artist and, since every couverture has a different aroma, chefs in the finest restaurants come to us. In fact, some French journalists call us the Moutin Rothschild of the chocolate world.”

Aptly, its chocolates include a line of Grand Cru and Extra Brut chef bars. The latest addition to Valrhona’s estate collection is Gran Couva Vintage chocolate bars. The label looks like one for a wine bottle.

Coming to America

The next leap for chocolate happened when Chocolates El Rey, an old Venezuelan company, came to the United States in 1995. Started in 1929, El Rey is owned by one family–the Redmond/Schlageters. It employs European technology and, according to Presilla, who once represented El Rey, is the most progressive chocolate manufacturer in South America. Jorge Redmond, the current president, was born in Venezuela but has Swiss roots. His father was from Louisiana, attended to Rice University in Houston, and eventually went to Venezuela with Exxon.

When trying to break into the American market, the company took a different approach by single-handedly starting a public education program about cacao beans and practices for making fine chocolate. Consumers started to pay attention.

Cacao originated somewhere between southern Mexico and northern South America, so even if Venezuela was not the site of origin, it is blessed with a combination of temperature, soil, and rainfall that creates ideal conditions for cultivation. Hence, El Rey doesn’t have to import cacao; it’s an indigenous resource.

There are three types of cultivated cacao: the criollo, a delicate and lower producing heirloom bean; the forastero, a sturdy, disease-resistant Amazonian cacao favored by large commercial plantations in Africa, Asia, and Brazil; and the trinitario, a cross between criollo and forastero with high-quality flavor that retains the hardiness of the forastero. All three thrive in Venezuela, but the chocolates El Rey exports to the United States are of single origin–the Carenero Superior, a stalwart bean grown northeast of Caracas.

El Rey was also a front-runner in educating its network of small cacao farmers about proper fermentation. Many farmers just spread the beans out on the road, set up a makeshift barrier so that no one will run over them, and proceed with sun drying. But proper fermentation takes anywhere from two to six days, depending on the quality of the bean and the weather. Premature drying truncates the process by 25–40 percent, which affects ultimate flavor. A lot of other things affect fermentation as well. Some farmers ferment cacao beans by heaping them on the ground and covering them with plantain leaves, while some aerate and rotate. Any nuance at this stage–and, for that matter, any other stage–will affect the final taste. El Rey ferments its chocolate in wooden boxes made specifically for that purpose.

El Rey’s chocolates–Gran Saman, Apamate, Bucare, Mijao, Caoba–are named for the taller canopy trees that shade the shorter cacao trees planted in the 1600s. Its white chocolate–Icoa–is named after the mythical white Indian maiden who protected the forests of a cacao-producing area in eastern Venezuela.

American Artisans

I first read about Scharffen Berger chocolates in a Southwest Airlines inflight magazine. The story of John Scharffenberger, who sold his interests in a Californian sparkling wine company, and his partner Robert Steinberg, a physician in the middle of a career change, intrigued me. Friends for twenty years and looking for a challenging joint venture, they founded the only new American chocolate company in fifty years. When I first tasted these chocolates, I found them much stronger than others. This difference is largely attributable to their generally higher cocoa mass, or combined amount of cocoa and cocoa butter. A couple of the company’s products contain 70 percent or more.

Scharffen Berger (two words to distinguish it from Scharffenberger’s former wine company) works from the heart, selecting beans with full flavor. “I use the techniques I learned as a winemaker to put together a blend of cacao beans for our chocolates to make as an intense and fully saturated taste as possible,” explains Scharffenberger.

And the company cares about fermentation. “Fermentation is a key factor in our choosing beans,” says Scharffenberger. “When suppliers send us a one-kilo sample, we cut fifty beans in half with a guillotine-like device to look at the percentage of fermentation, which can be determined by color. Before we buy, we also check for any contamination and positive attributes like fruitiness and level of tannins.

“We are having an easy time marketing our products because of the lack of competition in the high-quality chocolate category. There is a lot of demand and very few competitors.”

The line includes candy bars, chef bars of semisweet, bittersweet, and unsweetened chocolate, as well as cocoa powder and cacao nibs, which are roasted cocoa beans separated from their husks and broken into small bits. (Add a tablespoon of nibs to your next grinding of fresh coffee beans.)

In addition to making and selling chocolate, Scharffenberger, who has a degree in agricultural history, spends a lot of time educating the public about chocolate. He investigates the contextual history of food products as a whole, discussing where they come from and how they fit into a cultural background. He has taught chocolate courses at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Scharffen Berger* is not the only American thing happening. Guittard, a family-owned company based in Burlingame, California, is small enough to have personality. The current president, Gary Guittard, has used old family recipes to create a new line of chocolates dedicated to his grandfather, Etienne Guittard. Founded in 1868, Guittard has historically been a supplier to candy companies, and its sweet ground chocolate has been a favorite among San Francisco coffeehouses.

“We have survived because of our quality,” explains Guittard, who is also president of the Chocolate Manufacturers Association. “We got caught up in playing the games of the big companies and forgot our heritage. However, the growing interest in nouveau chocolates has piqued my interest, although it has taken a while to get back to our roots.”

He has been helped along in his efforts to redefine the company with the discovery of two old chocolate formula books belonging to his father and grandfather. “Unfortunately, some wonderful cacaos my ancestors used are no longer available, such as Bahian from Brazil,” laments Guittard. His new line of chocolates will range from 58 to 72 percent cacao and will take the form of one-kilo chef bars and discs.

What’s the future? Chocolate aficionados will want to know more about the chocolate they consume and whether it was produced by sustainable methods with good cacao. As Presilla says, “If a company is using good cacao, it will want to talk about it; if not, it will keep silent.” And there will continue to be a place for small importers and manufacturers, which are finding a niche in the gigantic chocolate market under the nose of the big guys. “As long as there are companies that want quality and are willing to pay a premium, small cacao farmers will have a job,” says Presilla.

Chocolate espresso brulées

For these creamy brulées, Maricel Presilla was inspired by the Cuban cortadito–a dark espresso toned down with a little frothy milk. Like the cortadito, these are a perfect end to a meal when served in 4-ounce commercial demitasse cups or ceramic ramekins and topped with crushed cacao nibs. Makes nine 4-ounce coffee brulées. (Used by permission of Maricel Presilla.)

- 1 whole egg

- 4 egg yolks

- 2 oz. sugar

- 1 cup heavy cream

- 1 cup whole milk

- 2 cinnamon sticks

- 3 star anise pods

- 1 vanilla bean, split open

- 1 tsp. vanilla extract

- 1/2 cup dark espresso

- 8 oz. milk chocolate (preferably El Rey’s Caoba or Valrhona’s Jivara)

- or a bittersweet chocolate ( El Rey’s Bucare, Scharffen Berger 60 percent,

- or Guittard Onyx), chopped fine

- 1 cup white sugar

- cacao nibs (preferably Scharffen Berger)

To make the chocolate espresso cream: Preheat oven to 335*F. Whisk the whole egg, egg yolks, and half the sugar together; set the mixture aside. In a saucepan, bring to a simmer the heavy cream, milk, and the rest of the sugar, cinnamon, star anise, vanilla beans, vanilla extract, and espresso. Remove the cinnamon sticks, star anise, and vanilla bean.

Turn off the heat and add the chopped chocolate. As it melts, whisk to combine. Do not overwhip! Gradually stir the warm chocolate mixture into the whisked eggs and combine thoroughly.

To bake the coffee brulées:Strain the mixture into a beaked container and pour into nine 4-ounce demitasse cups or ramekins. Place the cups or ramekins in a large baking pan. Place the pan in the middle rack of the preheated oven, and fill the pan with very hot water halfway up the sides of the ramekins. Bake at 335*F for 35 minutes or until set.

To caramelize the topping: Cool the ramekins to room temperature. Sprinkle each one with a little white sugar. Caramelize the sugar with a chef’s torch or under a broiler. Sprinkle about one-half teaspoon cacao nibs over the caramelized topping while still hot.

Double chocolate pudding

Lunch at the American Chemical Society’s chocolate conference was topped off with this splendid dessert fashioned by ACS chef Robert Dunn. He recommends Valrhona’s Equatoriale, which is 55 percent cacao. You will need four eight-ounce ceramic ramekins and a shallow baking pan for the water bath.

Pudding layer:

- 1 1/2 cups whipped cream

- 1/3 cup sugar

- 4 egg yolks

- 1 1/2 oz. semisweet chocolate (small pieces)”

Chocolate cake layer:

- 3 3/4 oz. semisweet chocolate

- 1/3 cup butter

- 3 eggs

- 1/4 cup sugar

To make the pudding layer: Place cream in a saucepan and bring to a boil. Meanwhile, whisk together the yolks and sugar. Remove the cream from the heat and pour over chocolate. Stir until melted. Slowly temper the cream into the yolk mixture. Pour into the ramekins, no more than half full. Bake in water bath at 300*F for 45 minutes, or until it jiggles when lightly touched. Cool completely.

To make the cake layer: Melt chocolate and butter in a double boiler. Whip the eggs and sugar on high speed until lemon yellow in color. Pour the chocolate/butter mixture into the eggs while still mixing. Divide batter over the pudding layer. Bake in a water bath at 325*F for 30–40 minutes, or until toothpick inserted just in the cake layer comes out clean. Serve warm with honey ice cream, or chill completely.

*Update: Scharffenberger is no longer an independent operation, but rather it is owned by Hershey’s.

Chocolate sources:

Chocolates El Rey

(830) 997-2200

www.chocolates-elrey.com

Guittard Chocolate

(650) 697-4427

www.guittard.com

Valrhona

(310) 277-0401

www.valrhona.com

Bernard Callebaut

1-800-661-8367

www.bernardcallebaut.com

For one of the best chocolate-selling Web sites see www.chocosphere.com

And then, there is Max Brenner, native of Israel, who has two chocolate stores in the United States, one in Manhattan and the other in Philadelphia. He also has a new chocolate cookbook, entitled Chocolate: A Love Story. He happened to be in the Philly store when I stopped by today (November 19, 2009). I bought his cookbook, he autographed it for me with the words, “WITH PURE CHOCOLATE LOVE, MAX, and I took this picture. I just love the layout and design of the store…not to mention the define chocolate. I ordered a Mexican hot chocolate. Yum.

Max Brenner

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

212-388-0030

1500 Walnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 10003

215-344-8150

Additional reading:

Maricel Presilla, The New Taste of Chocolate, Ten Speed Press, San Francisco, 2001.

Angus Wright, “Pesticides, Social Justice, and Biological Diversity on Brazil’s Cocoa Plantations,” Global Pesticide Campaigner, September 1994.

Lead photo of cocoa pod downloaded from The Food of the Gods: A Popular Account of Cocoa, Brandon Head, LONDON: R. BRIMLEY JOHNSON, 1903,http://www.gutenberg.org/files/16035/16035-h/16035-h.htm

A version of this article first appeared in the February 2001 issue of The World & I.